03 Feb There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly

I‘m skipping to my dissertation conclusion today because i’m reading Birth of Biopolitics – Foucault always makes me want to write – which is why i don’t read him before bed.

Regardless…

In my quest to reframe the “number of precise ways of governing with their correlative institutions” (F, 5) for the 21st century and what i’m sussing out as a new mode of capitalist production (i will, by golly, get Marx and Foucault into bed together, once and for all), i landed at the Department of Homeland Security.

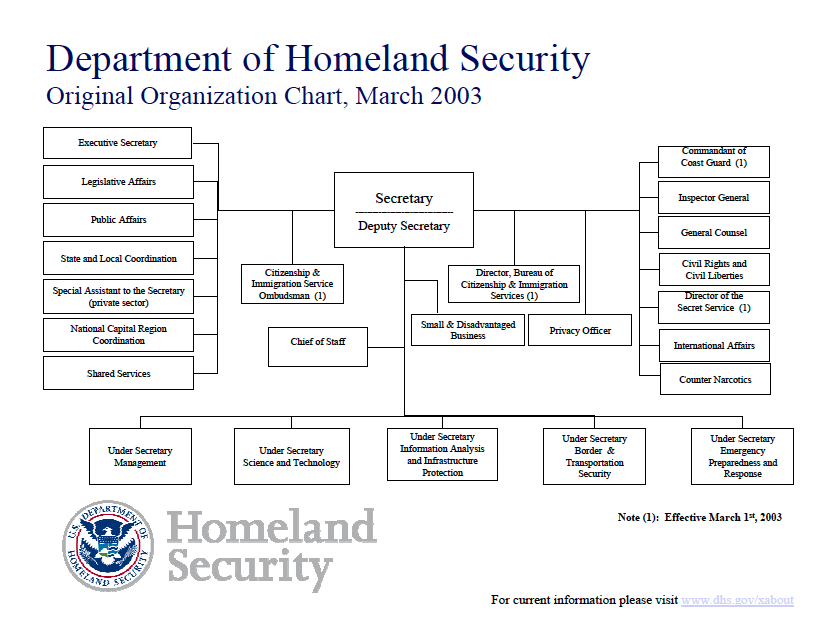

DHS came into existence just 11 days after September 11, 2001 attacks on NYC and the Pentagon. It came into being as a stand-alone in November 2002 (Public Law 107-296). This genealogy, is important. That was 13 months until it was an official department. The mandate, in 2001 and today, of DHS is to “secure the nation from the many threats we face.” Those threats, today, are managed through 22 additional departments an agencies that come under DHS. They span across several functions of government – from military (the U.S. Coast Guard no longer comes under DoD, but under DHS), Treasury, Justice, Transportation, Agriculture, FEMA, Energy, FBI, and the Secret Service. Each of the individual organizations have their own sets of directives. For instance, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center “has oversight and program management responsibilities at the International Law Enforcement Academies (ILEA) in Gaborone, Botswana, and Bangkok, Thailand. The FLETC also supports training at other ILEAs in Hungary and El Salvador.”

Interestingly, the Department of Health and Human Services was dragged into DHS, then pushed back out in 2004. However, there is still an Office of Health Affairs, which “serves as the Department of Homeland Security’s principal authority for all medical and health issues.” I’d be curious to learn the reasonings… I landed on this page while writing about the National Strategy for Pandemic Flu.

In 2005, Homeland Security released the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza – a guide and strategy for preparedness against a possible avian flu (or other variation, though the focus is largely on a strategy against avian flu) linking “a farmyard overseas to a living room in America” (Homeland Security Council (U.S.) 2005, 3). Six months later, the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza – Implementation Plan was released. The 227 pages document attempts to tackle the entire range of necessary responses to the potentiality of an influenza pandemic from medical to geopolitical, from economic to zoonotic. Like all good outbreak stories, the Plans’s outbreak narrative begins innocuously enough with tales of illness and deaths in exotic places, transmitting between exotic animals and their exotic caretakers. There is then the slow encroachment on Europe, and finally, through the imagined future possibilities, “[u]ncertainty will drive many of the outcomes we fear, including panic among the public, unpredictable, and unilateral actions by governments, instability in markets, and potentially devastating impacts on the economy” (Homeland Security Council (U.S.) 2006, 19–20). This potential for total breakdown of society leads, then, to an obvious outcome:

While the initial events leading to a deliberate or natural outbreak of infectious disease are dramatically different, the actions necessary to prepare, provide early warning, and respond are nearly identical. We should make this principle explicit in our planning for outbreaks and ensure, to the extent possible, that the mechanisms that we put in place are mutually supportive. This has clear implications for the manner in which the Federal Government directs its biodefense resources, but it similarly places responsibility upon the public health community to ensure that the infrastructure established at the State, local, and tribal levels to support traditional public health priorities is configured to meet our biodefense requirements (2006, 20–21).

First among the “Necessary Enablers of Pandemic Preparedness” is the need to “view pandemic preparedness as a national security issue” (Homeland Security Council (U.S.) 2006, 18).

In the event of a pandemic, the transmissibility of influenza viruses, the universal susceptibility of the world’s population to viruses that have not previously circulated, and the mobility of human populations mean that every corner of the globe and every element of society are likely to be touched. This has ramifications not only for the health and well being of populations, but for the national and economic security of nations, and the functioning of society (Homeland Security Council (U.S.) 2006, 18)

Chief among the responses, throughout the Strategy plan are various ways in which the pandemic will be contained via quarantine and travel restrictions.

This plan followed closely on the heels of a much larger policy turn. The 2005 DOD Directive 3000.05,[1] Military Support for Stability, Security, Transition, and Reconstruction (SSTR) Operations[2] marked a major strategic shift in U.S. military policy in that stability operations[3] were given equal importance to combat operations, stating “a core U.S. military mission that the Department of Defense shall be prepared to conduct with proficiency equivalent to combat operations.”

And here is where we begin to tie these threads together – the policing function and the military-diplomatic function of the state, or at least its attempts to govern according to its raison.

[1] DoD directives are broad policy documents which establish or describe policy, programs, and organizations; define missions; provide authority; and assign responsibilities. DoD Instructions implement the policy or prescribes the manner or a specific plan or action for carrying out the policy, operating a program or activity, and assigning responsibilities.

[2] Previously, these were known as Complex Contingency Operations under the 1997 PDD/NSC 56.

[3] The Department of Defense, in the 2009 Instruction, defines stability operations as, “an overarching term encompassing various military missions, tasks, and activities conducted outside the United States in coordination with other instruments of national power to maintain or reestablish a safe and secure environment, provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief” (1). These missions, tasks, and activities, according to the 2011 JCoS Stability Operations doctrine, come in three broad categories: initial response activities, transformational activities, and sustainment activities (vii-viii).

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.